Ch…ch…ch…changes….Part 1

31 Aug 2011

I was never very good at getting my head around new technologies very quickly. I’m a slow learner about certain things. For example, every time I get a new cell phone, and since 1988 or so, I’ve had dozens of different models, it takes me several weeks to actually like my new device. Interestingly, to this day, I only upgraded to an iPhone 3 because my original iPhone got thrown in the washer with my jeans. I hadn’t planned on buying a new iPhone model until it hit double digits. iPhone 10…. Now you’re talking. And when I do buy that device, it too will take me a month or so before I like it.

When I first started at ILM, we were in the throws of working on WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT. I had come over to ILM from heading up a video post production company called One Pass Film and Video. I was never really sure why we called it “Film and Video”. We had a Rank Cintel telecine, which transferred film to video, but generally speaking we were all about video.

So, when I started at ILM, I was shocked to find out that there was no video, no computers to speak of (except for this strange device called a PIXAR cube) and that everything was being done in 35mm VistaVision film. Celluloid strips with sprocket holes, what a concept.

We sent all our exposed film to a local San Francisco lab called Monaco. And we sent LOTS of it… not length but quantity. Every take we did was about 5 seconds or so of film. On certain films with certain directors there were literally hundreds of iterations and at times, on a really big show, a hundred or more shots. Our runners would minimally make two trips a day from Marin to SF to shuttle these 150 frames per shot to the lab. And we would wait for some time to get them back so that our teams could view them.

There was also this nasty little problem called grain structure. Every time an element was made, and then needed to be composited using an optical printer, re-photographing the elements, the resulting composite now had to be sent to the lab and processed. That process resulted in creating “film noise” or additional grain structure and if one processed enough elements and re- photographed them enough times, the image looked terrible. Which is why most of the elements were photographed using 35mm VistaVision.

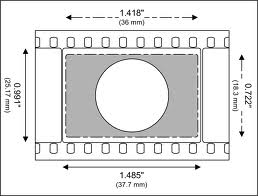

VistaVision is similar to the film in a typical old school SLR where film travels through the gate horizontally, as opposed to vertically like traditional motion picture film. The result is that the negative exposed in VistaVision is 8 perf not 4 perf, thereby having a much larger negative area and reducing the level of grain.

VistaVision is similar to the film in a typical old school SLR where film travels through the gate horizontally, as opposed to vertically like traditional motion picture film. The result is that the negative exposed in VistaVision is 8 perf not 4 perf, thereby having a much larger negative area and reducing the level of grain.

It’s sorta easy for me now as I’ve had about a quarter of a century to fully “grok” the process, but my first couple of weeks I was lost in the ozone. I couldn’t quite understand why we were not using “Quantel type devices” as we were when I was running One Pass. In video, the digital revolution had already started. In video we already had transputer based digital post production tools. Paintboxes where an artist could easily alter a frame of video. “Quantel Harry’s” where we could now alter multiple frames in a running clip. A fairly user friendly Graphical User Interface allowing true artists to manipulate images.

At ILM there had been some pretty remarkable technical advances in film technologies. The motion control camera, allowing for computer controlled stepper motors to drive repeatable camera moves. The multi head optical printer allowing for multi element exposures in optical compositing. The multi plane matte camera. The motion controlled down shooter animation stand. Advances in blue screen photography. And in the mid 1980’s the PIXAR transputer, the breadbox film scanner, Renderman software and then…. it just stopped.

By the time I got to ILM there had been a freeze on capital spending. Pixar was sold to Steve Jobs. Technology advances were effectively prohibited by LucasFilm. There were very few personal computers. Some had client terminals attached to servers. All in all, ILM was frozen in time back in 1980, yet this was now 1989 and something had to be done.

I did what I always did. I paid no attention to the powers that be. The Ranch forbade ILM from buying any new equipment. Yet I rallied the top creative and technical personnel at ILM and I started approving a substantial capital equipment budget. We built new VistaVision cameras, we started purchasing personal computers by the score and we negotiated an agreement with Pixar that gave us a perpetual site license for Renderman and access to a film to digital data scanner.

With my video post experience, I had a relationship with Quantel, the Newberry UK transputer based digital video technology company. Additionally, being ILM, we also had a relationship with Kodak as well as access to Celco film recorders, a digital to film recording device.

I saw an opportunity that was analogous to what was starting to happen in personal computing as well as video post production. An input device ( the keyboard in a pc world, a telecine in a video post world, a fax machine in telephony), a well designed Graphical User Interface ( the Mac OS in the pc world, A Harry/Paintbox in the video post world) and finally an output device ( a printer in the PC world, videotape in the video post world). It seemed a possibility to me ( and several others… John Knoll and Dennis Muren to name but two, who fully got it) that a similar system could be designed for film post production and visual effects.

I proceeded to initiate conversations between Quantel ( the GUI player) and Kodak ( which had developed a reasonably stable, tri linear array CCD film scanning device). I asked Quantel to host a meeting at their headquarters in England where the various technologies could be discussed in the hopes of a collaboration that would allow for a complete and integrated solution for the digital manipulation of high resolution moving images.

Everyone agreed that we should gather in Newberry England. Unfortunately each corporate participant had a very different take on the concept of collaboration. I had hoped that Kodak would provide the input device, Quantel the GUI, Celco the output device and SGI the graphics engine. As ILM’s GM, and the initiator of this get together, I tried for several hours to get each company to understand that we were all on the brink of a technological revolution. I had traveled across multiple time zones, flew in airliners and helicopters to help these people see how exciting this could be…

Everyone agreed that we should gather in Newberry England. Unfortunately each corporate participant had a very different take on the concept of collaboration. I had hoped that Kodak would provide the input device, Quantel the GUI, Celco the output device and SGI the graphics engine. As ILM’s GM, and the initiator of this get together, I tried for several hours to get each company to understand that we were all on the brink of a technological revolution. I had traveled across multiple time zones, flew in airliners and helicopters to help these people see how exciting this could be…

But, with typical corporate sensibilties, Kodak and Quantel both decided to offer their own proprietary turn key solutions. Kodak formed Cineon (a computer system, augmented by film scanning and recording hardware, designed by Kodak, for digital intermediate film production. It included a scanner, tape drives, workstations with digital compositing software, and a film recorder. The system was first released in 1993 and was abandoned by 1997) and Quantel decided to do the same ( Domino ) which met with the same fate.

Luckily, with the help of the likes of George Joblove, Doug Kay, Scott Squires, Nancy St. John, Dennis Muren, John Knoll and Ed Jones, we were able to cobble together what was needed to put a technology strategy in place. We entered into strategic agreements with Kodak for their CCD scanner, Alias for their sofware and SGI for their early UNIX based graphics platforms. Additionally we had our agreements with Pixar for their Renderman rendering application, and John Knoll and his brother Tom had been developing this new application for color space and digital image manipulation.

John Knoll called me one day and asked whether he and his brother could incorporate some of the know how that had been developed over the years at ILM in their new software application for photography. Though I was the GM at ILM, I needed “Ranch” approval regarding any issues dealing with legal matters, in this case, ILM intellectual property that John wanted to use.

I tried contacting George’s office directly because I assumed that Doug Norby, Lucasfilm’s president would be, as usual, difficult to deal with. I placed several calls to GWL through his assistant Jane Bay. George never called back. Finally, Jane Bay called and told me that GWL felt fine about allowing John Knoll to use ILM’s IP, since, as Jane said… “it probably wont amount to much anyway”.

Not much at all…..it was called Photoshop.